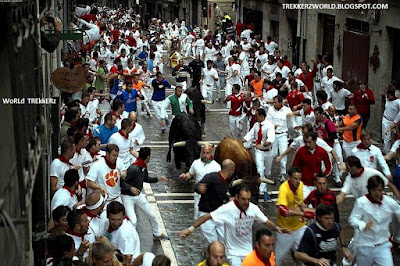

Running of the Bulls

Running of the Bulls Festival

The most famous running of the bulls is held during the eight-day festival of Sanfermines in honour of Saint Fermin in Pamplona,

although they are also traditionally held in other places such as towns and villages across Spain,

Portugal, in some cities in Mexico,and southern France during the summer.

The origin of this event comes from the need to transport the bulls from the fields outside the city,

where they were bred, to the bullring, where they would be killed in the evening.

During this 'run', youngsters would jump among them to show off their bravado.

In Pamplona and other places, the six bulls in the event are still those that will feature in the afternoon bullfight of the same day.

Spanish tradition says the true origin of the run began in northeastern Spain during the early 14th century.

While transporting cattle in order to sell them at the market, men would try to speed the process by hurrying their cattle using tactics of fear and excitement.

After years of this practice, the transportation and hurrying began to turn into a competition, as young adults would attempt to race in front of the bulls and make it safely to their pens without being overtaken.

When the popularity of this practice increased and was noticed more and more by the expanding population of Spanish cities, a tradition was created and stands to this day.

Pamplona bull run

The Pamplona encierro is the most popular in Spain and has been broadcast live by RTVE,

the public Spanish national television channel,

for over 30 years. It is the highest profile event of the San Fermin festival,

which is held every year from 6–14 July.

The first bull running is on 7 July,

followed by one on each of the following mornings of the festival,

beginning every day at 8 am.

Among the rules to take part in the event are that participants must be at least 18 years old,

run in the same direction as the bulls, not incite the bulls, and not be under the influence of alcohol.

Fence

In Pamplona a set of wooden fences is erected to direct the bulls along the route and to block off side streets.

A double wooden fence is used in those houses where there is enough space for it,

while in other parts the buildings of the street act as barriers.

The gaps in the barricades are wide enough for a human to slip through, but narrow enough to block a bull.

The fence is composed of around three thousand separate pieces and while some parts are left for the duration of the fiesta others are mounted and dismounted every morning.

Spectators can only stand behind the second fence,

whereas the space between the two fences is reserved for security and medical personnel and also to participants who need cover during the event.

Preliminaries

The encierro begins with runners singing a benediction.

It is sung three times,

each time being sung both in Spanish and Basque.

The benediction is a prayer given at a statue of Saint Fermin,

patron of the festival and the city,

to ask the saint's protection and can be translated into English as

"We ask Saint Fermin, as our Patron, to guide us through the encierro and give us his blessing".

The singers finish by shouting

"Viva San Fermín!, Gora San Fermin!"

("Long live Saint Fermin", in Spanish and Basque).

Most runners dress in the traditional clothing of the festival which consists of a white shirt and trousers with a red waistband ("faja") and neckerchief ("pañuelo").

Also some of them hold the day's newspaper rolled to draw the bulls' attention from them if necessary.

The running

A first rocket is set off at 8 a.m. to alert the runners that the corral gate is open.

A second rocket signals that all six bulls have been released. The third and fourth rockets are signals that all of the herd has entered the bullring and its corral respectively, marking the end of the event. The average duration between the first rocket and the end of the encierro is two minutes, 30 seconds.

The encierro is usually composed of the six bulls to be fought in the afternoon, six steers that run in herd with the bulls, and three more steers that follow the herd to encourage any reluctant bulls to continue along the route.

The function of the steers, who run the route daily, is to guide the bulls to the bullring.

The average speed of the herd is 24 km/h (15 mph).

The length of the run is 875 meters (957 yards). It goes through four streets of the old part of the city (Santo Domingo, Ayuntamiento, Mercaderes and Estafeta) via the Town Hall Square and the short section "Telefónica" (so named for the mobile phone operator located at the intersection) just before entering into the bullring through its callejón (tunnel).

The fastest part of the route is up Santo Domingo and across the Town Hall Square, but the bulls often became separated at the entrance to Estafeta Street as they slowed down.

One or more would slip going into the turn at Estafeta ("la curva"),

resulting in the installation of

anti-slip surfacing,

and now most of the bulls negotiate the turn onto Estafeta and are often ahead of the steers.

This has resulted in a quicker run. Runners are not permitted in the first 50 meters of the encierro,

which is an uphill grade where the bulls are much faster.[citation needed]

Injuries, fatalities and sanitary attention

Every year, between 50 and 100 people are injured during the run.

Not all of the injuries require taking the patients to the hospital:

in

2013 50 people

were taken by ambulance to Pamplona's hospital, with this number nearly doubling that of 2012.

Goring is much less common but potentially life threatening.

In 2013 for example, 6 participants were gored along the festival,

in 2012 only 4 runners were injured by the horns of the bulls with exactly the same number of gored people in 2011,

9 in 2010 and 10 in 2009; with one of the later killed.

As most of the runners are male, only 5 women have been gored since 1974.

Previously to that date running was prohibited for women.

Another major risk is runners falling and piling up (a "montón") at the entrance of the bullring ,

which acts as a funnel as it is much narrower than the previous street.

In such cases injuries come both from asphyxia and contusions to those in the pile and from goring if the bulls crush into the pile.

This kind of blocking of the entrance has occurred at least ten times in the history of the run,

the last occurring in 2013 and the first dating back to 1878.

A runner died of suffocation in one such pile up in 1977.

Overall, since record-keeping began in 1910, 15 people have been killed in the bull running of Pamplona, most of them due to being gored.

To minimize the impact of injuries every day 200 people collaborate in the medical attention.

They are deployed in 16 sanitary posts (every 50 metres on average), each one with at least a physician and a nurse among their personnel. Most of these 200 people are volunteers, mainly from the Red Cross.

In addition to the medical posts, there are around 20 ambulances.

This organization makes it possible to have a gored person stabilized and taken to a hospital in less than 10 minutes.

15 Deaths since 1910 in the bull run of Pamplona

Year Name Age Origin Location Cause of death

1924 Esteban Domeño 22 Navarre, Spain Telefónica Goring

1927 Santiago Zufía 34 Navarre, Spain Bullring Goring

1935 Gonzalo Bustinduy 29 San Luis Potosí, Mexico Bullring Goring

1947 Casimiro Heredia 37 Navarre, Spain Estafeta Goring

1947 Julián Zabalza 23 Navarre, Spain Bullring Goring

1961 Vicente Urrizola 32 Navarre, Spain Santo Domingo Goring

1969 Hilario Pardo 45 Navarre, Spain Santo Domingo Goring

1974 Juan Ignacio Eraso 18 Navarre, Spain Telefónica Goring

1975 Gregorio Gorriz 41 Navarre, Spain Bullring Goring

1977 José Joaquín Esparza 17 Navarre, Spain Bullring Suffocated in a pile-up.

1980 José Antonio Sánchez 26 Navarre, Spain Town Hall Square Goring

1980 Vicente Risco 29 Badajoz, Spain Bullring Goring[

1995 Matthew Peter Tassio 22 Glen Ellyn, Illinois, USA Town Hall Square Goring

2003 Fermín Etxeberria 62 Navarre, Spain Mercaderes Hit by a horn

2009 Daniel Jimeno Romero 27 Alcalá de Henares, Spain Telefónic Goring

Dress code

Though there is no formal dress code,

the very common and traditional attire is white pants,

white shirt with a red scarf around the waist and a red handkerchief around the neck.

The majority of runners are similarly dressed, many times with red wine stains from the previous night or earlier in the festival.

Another common dress practice, seen as a risk by some but as a daring depiction of courage by others is dressing in a conspicuous manner.

Many runners that want to be perceived as daring wear colors other than white,

a common alternate color choice is blue.

Blue is thought by some to draw the bulls' attention.[citation needed]

Others include large logos on their shirt to capture the attention of the bulls.

In the age of social media explosion, this also thought to be a way to highlight someone in a photo.

Media

The encierro of Pamplona has been depicted many times in literature,

television or advertising,

but became known worldwide partly because of the descriptions of Ernest Hemingway in books

The Sun Also Rises and Death in the Afternoon.

The cinema pioneer Louis Lumière filmed the run in 1899.

The event is the basis for a chapter in James Michener's 1971 novel The Drifters.

The run is depicted in the 1991 Billy Crystal film City Slickers where the character "Mitch" (Crystal) is gored (non-fatally) from behind by a bull during a vacation with the other main characters.

The run appears in the 2011 Bollywood movie Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara,

directed by Zoya Akhtar, as the final dare in the bucket list of the three bachelors who have to overcome their ultimate fear; death.

At first, the trio run part of the route. They stop at the square,

but then recover their nerve,

and continue to the end.

The completion of the run depicts their freedom as they learn that surviving a mortal danger can bring joy.

Running with the Bulls,

a 2012 documentary of the festival filmed by Construct Creatives and presented by Jason Farrel,

depicts the pros and cons of the controversial tradition.

Since 2014 the Esquire Channel has broadcast the running of the bulls as a show in the US,

with both live commentary and then a recorded 'round up' later in the day by NBCSN commentators the Men in Blazers,

including interviews with noted participants such as

Madrid-born

runner David Ubeda,

former US Special Forces soldier turned filmmaker Dennis Clancey,the historic New York-born runner Joe Distler and former British bullfighter and author Alexander Fiske-Harrison.

In 2014, the eBook guide Fiesta:

How To Survive

The Bulls Of Pamplona caused headlines around the world when one of the contributors was gored by a bull soon after its publication.

(See Further Reading section below.)

Other examples

Although the most famous running of the bulls is that of San Fermín,

they are held in towns and villages across Spain, Portugal,

and in some cities in southern France during the summer.

Examples are the bull run of San Sebastián de los Reyes,

near Madrid,

at the end of August which is the most popular of Spain after Pamplona, the bull run of Cuéllar,

considered as the oldest of Spain since there are documents of its existence dating back to 1215,

the Highland Capeias of the Raia in Sabugal, Portugal,

with horses leading the herd crossing old border passes out of Spain and using the medieval 'Forcåo', or the bull run of Navalcarnero held at night.

Other encierros have also caused fatalities.

Bous al carrer

Bous al carrer, correbou or correbous

(meaning in Catalan, bulls in the street)

is a typical festivity in many villages in the Valencian region, Terres de l'Ebre,

Catalonia and Fornalutx, Mallorca. Another similar tradition is soltes de vaques,

where cows are used instead of bulls. Even though they can take place all along the year,

they are most usual during local festivals

(normally in August).

Compared to encierros, animals are not directed to any bullring.

These festivities are normally organized by the youngsters of the village,

as a way for showing their courage and ability with the bull. Some sources consider this tradition a masculine initiation rite to adulthood.

Stamford Bull Run

Main article: Stamford Bull Run

The English town of Stamford,

Lincolnshire was host to the Stamford Bull Run for almost 700 years until it was abandoned in 1837.

According to local tradition,

the custom dated from the time of King John when William de Warenne,

5th Earl of Surrey,

saw two bulls fighting in the meadow beneath.

Some butchers came to part the combatants and one of the bulls ran into the town,

causing a great uproar.

The earl, mounting his horse, rode after the animal,

and enjoyed the sport so much, that he gave the meadow in which the fight began,

to the butchers of Stamford,

on condition that they should provide a bull,

to be run in the town every 13 November,

for ever after.

As of 2013 the bull run had been revived as a ceremonial, festival-style community event.

Mock bull runs

A variation is the nightly

"fire bull"

where balls of flammable material are placed on the horns.

Currently the bull is often replaced by a runner carrying a frame on which fireworks are placed and dodgers,

usually children, run to avoid the sparks.

In 2008 Red Bull Racing driver David Coulthard and Scuderia Toro Rosso driver Sébastien Bourdais performed a version of a 'bull running' event in Pamplona, Spain,

with the Formula One cars chasing 500 runners through the actual Pamplona route.

The Big Easy Rollergirls roller derby team has performed a version of annual bull run in New Orleans,

Louisiana since 2007.

The team, dressed as bulls, skates after runners through the French Quarter.

In 2012 there were 14,000 runners and over 400 "bulls" from all over the country,

with huge before- and after-parties.

In Ballyjamesduff,

Ireland, an annual

"Pig Run"

is held with small pigs.

It looks just like mini-encierro but with pigs instead of bulls.

In Dewey Beach,

Delaware, the Starboard bar sponsors an annual Running of the Bull [sic],

in which hundreds of red and white-clad beachgoers are chased down the shore by a single "bull"

(two people in a costume).

In Rangiora,

New Zealand, an annual

"Running of the Sheep"

is held.

Where 1000–2000 sheep are released down the main street of the small farming town.

In 2014,

Pamplona inaugurated a series of running events in June,

the San Fermin Marathon, of a full marathon (42.195 km),

half marathon (21.097 km), or 10 km road race that concludes with the final 900m of each race using the encierro route,

runners crossing the finish line inside the bullring.

Opposition

Many opponents argue that bulls are mentally injured by the harassment and voicing of both participants and spectators,

and some of animals may also die because of the stress,

especially if they are roped or bring flares in their horns (bou embolat version).

Despite all this, the festivities seem to have wide popular support in their villages

Many animal rights activists oppose the event. PETA activists created the "running of the nudes",

a demonstration done two days before the beginning of San Fermín in Pamplona.

By marching naked, they protested the festival and the following bullfight,

arguing the bulls are tortured for entertainment.

The city of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, cancelled its Sanmiguelada running of the bulls after 2006,

citing public disorder associated with the event.

also in the state of Guanajuato,

picked up the event.

It is now called La Marquesada and the three-day event is held during the last weekend of the month of September or first weekend of October.

Running of the Bulls | San Fermin | San Fermin Pamplona Spain

in the region of Navarra, every year from the 6th to the 14th of July.

They have become internationally known because of the running of the bulls,

where the bulls are lead through the streets of the old quarter as far as the bull ring by runners.

The fiestas are celebrated in honor of San Fermin,

patron saint of Navarra, although the religious aspect would seem to have taken on a secondary role over the last number of years.

Nowadays, the fiestas are seen as a mass gathering of people from all the corners of the world and where the partying,

the fun and the joy of it all are the most outstanding ingredients.

The Encierro ... The Running of the Bulls

The Encierro is the event at the heart of the Sanfermines and makes the fiesta a spectacle that would be unimaginable in any other place in the world.

It was born from need: getting the bulls from outside the city into the bullring.

The encierro takes place from July 7th to 14th and starts at the corral in Calle Santo Domingo when the clock on the church of San Cernin strikes eight o"clock in the morning.

After the launching of two rockets, the bulls charge behind the runners for 825 metres, the distance between the corral and the bullring.

The run usually lasts between three and four minutes although it has sometimes taken over ten minutes,

especially if one of the bulls has been isolated from his companions.

Chants to San Fermin

The bull run has a particularly emotional prelude.

It is when the runners,

just a few metres up the slope from the corral where the bulls are waiting,

raise their rolled newspapers and chant to an image of San Fermin placed in a small recess in the wall in the Cuesta de Santo Domingo.

Against the strongest of silences, the following words can be heard:

"A San Fermin pedimos, por ser nuestro patron,

nos guie en el encierro dandonos su bendicion."

(We ask San Fermin, being our patron saint, to guide us in the bull run and give us his blessing).

When they finish they shout

"Viva San Fermin!, Gora San Fermin."

This chant is sung three times before 8am first, then when there are five minutes to go before 8am, then three minutes and one minute before the gate of the corral is opened.

Rockets in the bullring

The third rocket, fired from the bullring, signals that all the bulls have entered the bullring. A fourth and final rocket indicates that all the bulls are safely in the corral located inside the bullring, and that the bull run has ended.

A fence of 3,000 parts

For security reasons, a double fence marks out the route of the bull run through the streets. It is made of over 3,000 wooden parts (planks, posts, gates, etc.). Part of the fence stays put throughout the fiesta but other sections are assembled and disassembled every day by a special brigade of workers.

The role of the pastores

A large number of pastores (bull "shepherds") cover the entire bull run. They place themselves behind the bulls, with their only protection being a long stick. Their main role is to stop the odd idiot from inciting the bulls from behind, to avoid the bulls turning round and running backwards, and to help any bulls that have stopped or have been separated from their companions to continue running towards the bullring.

The dobladores

Other key people in the bull run are the dobladores, people with good bullfighting knowledge (sometimes ex-bullfighters) who take up position in the bullring with capes to help the runners "fan out" (in other words, run to the sides after they enter the bullring) and "drag" the bulls towards the corral as quickly as possible.

The two groups of mansos (bullocks)

The six fighting bulls that will take part in the evening bullfight start the run accompanied by an initial group of mansos, which act as "guides" to help the bulls cover the route. Two minutes after leaving the corral in Santo Domingo, a second group of bullocks (the so-called "sweep-up" group), which are slower and smaller than the first one, are let out to lead any bulls that might have stopped or been left behind in the bull run towards the bullring.

Useful information about the bull run

The encierro is an unrepeatable experience for spectators and runners alike. It is a spectacle that is defined by the level of risk and the physical ability of the runners.

An inexperienced runner should learn about the characteristics of this dangerous "race" (although it should not be considered as a race) before starting, and also about the protective measures to be taken for his/her own safety and that of the people running alongside.

Not everyone can run the encierro. It requires cool nerves, quick reflexes and a good level of physical fitness. Anyone who does not have these three should not take part. It is a highly risky enterprise.

Runners should start somewhere between the Plaza del Ayuntamiento (City Hall Square) and the pink-slab Education building in the Cuesta of Santo Domingo, and they should be there before 7:30am because entry to the run is closed from that time on. The rest of the run, except for the stretch mentioned above, must be completely clear of runners until a few minutes before 8am.

What is not allowed in the bull run

People under 18 years of age, who must not run or participate.

Crossing police barriers placed to ensure that the run goes off smoothly.

Standing in areas and places along the route that have been expressly prohibited by the municipal police force.

Before the bulls are released, waiting in corners, blind spots, doorways or in entrances to other establishments located along the run.

Leaving doors of shops or entrances to apartments open along the route.

The responsibility for ensuring these doors are closed lies with the owners or tenants of the properties.

The responsibility for ensuring these doors are closed lies with the owners or tenants of the properties.Being in the bull run while drunk, under the effects of drugs or in any other improper manner.

Carrying objects that are unsuitable for the run to take place correctly.

Wearing inappropriate clothes or footwear for the run.

Inciting the bulls or attracting their attention in any manner, and for whatever reason, along the route of the run or in the bullring.

Running backwards towards the bulls or running behind them.

Holding, harassing or maltreating the bulls and stopping them from moving or being led to the pens in the bullring.

Stopping along the run and staying on the fence, barriers or in doorways in such a way that the run or the safety of other runners is jeopardised.

Taking photographs inside the run, or from the fences or barriers without due authorisation.

Carrying objects that are unsuitable for the good order and security of the bull run.

Installing elements that invade horizontal, vertical or aerial space along the bull run, unless expressly authorised by the Mayor"s Office.

Any other action that could hamper the bull run taking place normally.

Why running with the bulls is more than a deathwish

The jitters are forgivable. We know what’s coming. Although we don’t really, not precisely. This is an unpredictable business. We look at our phones and watches for a final time.

The jitters are forgivable. We know what’s coming. Although we don’t really, not precisely. This is an unpredictable business. We look at our phones and watches for a final time.At 8am a rocket sounds. A gate opens in our heads, and nightmares briefly swarm. A few beats later a second rocket goes off, and panic takes over. Before we know it they’re upon us, although we don’t see them immediately. The first wave is human, and that wave breaks when its legs give out, unable to outrun six peak-condition fighting bulls and their guiding steers.

In turn, we move, scattering like thrown dice, trying our luck, some of us ahead of the herd for meaningful seconds, others falling, under feet and hooves, or flattening themselves against the wall, wishing they were shadows or smoke.

A glancing blow from one of these horns will open you up like a present. And so it continues, section by section for just over half a mile, the bulls averaging half a ton and 15mph – even on these winding streets – and the runners, ordinary Joes and athletes alike, hoping that whatever god or philosophy they cling to is paying attention. And that medical help is standing by.

That’s right, I’m in Pamplona, in the Navarre region of Spain, on the second day of the 426-year-old festival of San Fermín, which is held each year from July 6 to July 14 and has the encierro, or bull run, at its heart. There is a run each morning from July 7. It starts at the foot of Calle Santo Domingo, where the bulls are released from their holding pen to chase a couple of thousand people for between two and five minutes, and finishes in the bullring, where the bulls meet their end that afternoon. The run has followed this route since 1852.

That’s right, I’m in Pamplona, in the Navarre region of Spain, on the second day of the 426-year-old festival of San Fermín, which is held each year from July 6 to July 14 and has the encierro, or bull run, at its heart. There is a run each morning from July 7. It starts at the foot of Calle Santo Domingo, where the bulls are released from their holding pen to chase a couple of thousand people for between two and five minutes, and finishes in the bullring, where the bulls meet their end that afternoon. The run has followed this route since 1852.Foreign news coverage of the event is generally cartoonish, recounting – often with ill-concealed relish – the gorings and hospitalisations of the runners (there have been 16 fatalities since 1910), and painting Pamplona as an open asylum where idiocy and cruelty combine, to the disgust of anyone interested in animal rights.

Despite the growing popularity of bullrunning as an extreme sport among foreigners, the Spanish still generally make up the lion's share of the participants.

Despite the growing popularity of bullrunning as an extreme sport among foreigners, the Spanish still generally make up the lion's share of the participants.But the festival is more than its displays of foolhardiness, as indeed it would have to be to account for the number of people who return to it year after year.

I’m one of those recidivists. I’ve clocked up three visits, which in San Fermín terms means I’m still cutting my teeth, but I consider myself a lifer. When I’m asked about its appeal, outside of fiesta, I hum and haw, as though I don’t want to expose its magic to the cold light of day. But once I’m there, answers come easily. Of course, no one puts the question to me here because they’re here too, full of the same answers.

For nine days a sedate, conservative town of about 200,000 people is taken over… by itself. It opens wide and never closes. The veil is drawn back. Yes, the streets are awash with wine and patxaran, but also with fireworks, marching bands and dancing giants. It’s a Club 18-months-to-90 holiday, without a fist-fight in sight. (The 3,500-strong police presence doubtless helps.)

This extraordinary act of self-possession, in honour of a saint who, legend has it, was tied to a bull by his feet and dragged to his death, is witnessed by more than a million visitors a year. Its traditions run deeper than any tourist trap’s, though, so it is the intruders’ job to adapt to them.

This extraordinary act of self-possession, in honour of a saint who, legend has it, was tied to a bull by his feet and dragged to his death, is witnessed by more than a million visitors a year. Its traditions run deeper than any tourist trap’s, though, so it is the intruders’ job to adapt to them.Larry Belcher, a Texan rodeo rider turned university professor, warms to this romantic theme.

‘It’s like Brigadoon. It rises from nowhere. It’s its own world, and it changes everyone that stops by. Then it disappears before the regular world has had the chance to penetrate it.’ Larry comes alive when he says this, and he knows whereof he speaks. He has been running with the bulls of San Fermín for almost 40 years.

The Plaza del Castillo, the drawing room of Pamplona, is filling up after the encierro. Families seek coffee in the shade of the arcades, while gap-year students, in states of nervous exhaustion and T-shirts flushed with sangria from yesterday’s opening ceremony, pass out on browning grass beneath pom-pom plane trees.

The Plaza del Castillo, the drawing room of Pamplona, is filling up after the encierro. Families seek coffee in the shade of the arcades, while gap-year students, in states of nervous exhaustion and T-shirts flushed with sangria from yesterday’s opening ceremony, pass out on browning grass beneath pom-pom plane trees.The Pamplonicans are uniformly dressed in their whites with a red sash and pañuelo neckerchief, but the guiris – the not-too-gently mocking Spanish term for foreigners – have started to take a few liberties with the dress code.

Outside Bar Txoco, I’m looking for friends who took to the cobbles this morning. Keeping me company is Geoff Wanless, a painter and decorator from South Shields who turned 50 today and ran as his present to himself. When I ask him what San Fermín is doing on his bucket list, he says,

‘I’m having a midlife crisis and can’t afford a Porsche.’

I do a mental register to keep track of my friends, and within half an hour every runner I know is accounted for, holding their post-run glasses of cognac and flavoured milk.

I do a mental register to keep track of my friends, and within half an hour every runner I know is accounted for, holding their post-run glasses of cognac and flavoured milk.I breathe easier, letting the same drink have its way with my adrenalin, which is still cartwheeling. Nobody wants a repeat of last year, when Bill Hillmann, a fine runner who showed me the ropes when I was a new recruit, was gored in the thigh, just shy of his femoral artery.

It is Bill I see last, grinning broadly beneath his trademark duckbill cap, getting some help carrying a big lump of something. The 33-year-old Chicagoan props it against a table. It’s the stuffed and mounted bust of Brevito, the rogue bull (suelto) that almost did for him. Should the caves of Lascaux ever be turned into a bar it would make an impressive centrepiece.

I’ve heard of matadors decorating their bachelor pads with the heads of their worthier opponents, but never victims. Bill has much to thank Brevito for, though.

I’ve heard of matadors decorating their bachelor pads with the heads of their worthier opponents, but never victims. Bill has much to thank Brevito for, though.He used his time convalescing to write a memoir, Mozos: A Decade Running with the Bulls of Spain, and he casts his story of personal redemption in the form of the suelto.

‘Running with the bulls turned my life around,’ he says. ‘Before I came to Pamplona 10 years ago, I was in a gang, dealing drugs. Very violent. Totally lost. Sueltos are like that. Cut off from the herd. Full of fear and rage. A good runner can lead a runaway bull back to his herd. I wanted to be that runner. To rescue the bulls that rescued me.’

This may strike readers as sentimental anthropomorphism, but Bill is not alone in this.

This may strike readers as sentimental anthropomorphism, but Bill is not alone in this.For every 25 clueless, sleep-deprived package-tour drunks who think the encierro is just a lark, there is a runner who combines speed,

cunning and taurine psychology to get the most out of his time on the street and make it a safer place for man and beast alike.

(He can use a rolled-up newspaper – a staple of regular runners – to attract a rogue bull’s attention and sprint ahead of it in the hope that it will give chase, neatly avoiding carnage.)

That their efforts sometimes go awry is testament to the seriousness of the risks they take to try to make that happen.

There has been a tradition of foreigners running with the bulls, if in much smaller numbers, since the early 1950s. Unarguably the most celebrated of those trailblazers is Matthew Carney, a US Marine who fought at Iwo Jima.

There has been a tradition of foreigners running with the bulls, if in much smaller numbers, since the early 1950s. Unarguably the most celebrated of those trailblazers is Matthew Carney, a US Marine who fought at Iwo Jima.He died in 1988 of throat cancer – a disappointing way for him to bow out – but a thronged lunch is still held in his memory every fiesta. His daughter, Deirdre, 37, took up running relatively recently, though women on the course comprise a tiny minority and are usually first-timers in their 20s.

‘This is not a fiesta for “brave young men”,’ she says. ‘It’s a fiesta for everyone – the elderly, kids, mothers. This is a celebration about being alive, a play of chaos and ritual that everyone enjoys. Just because very few women run, it doesn’t mean we’re secondary characters here.’

I ask her about criticisms that Pamplona tacitly promotes an anything-goes ‘festival culture’, and mention the 19-year-old British woman who claimed to have been sexually assaulted by six men in the bathroom of a bar on the second day of the fiesta.

I ask her about criticisms that Pamplona tacitly promotes an anything-goes ‘festival culture’, and mention the 19-year-old British woman who claimed to have been sexually assaulted by six men in the bathroom of a bar on the second day of the fiesta.‘I personally feel incredibly safe here,’ she says, ‘but I’m older now and don’t party in the backstreets at 3am. In the 1990s, when I was 18 to 25, I used to get grabbed a lot in the street, to the extent that I realised I couldn’t wear a skirt.

Things have improved enormously. There have been huge campaigns against sexual assault in recent years. Rightly so. It bears repeating, we are not the sidekick or accoutrement of men having their fiesta. It’s ours, too. We can run the bulls if we want. We’re not here for decoration.’

At the breakfast tables in Calle Merced a few days later I hear someone refer to San Fermín as ‘Hemingstein’ – that is, a monster of Ernest Hemingway’s making (although it was also one of his favourite boyhood nicknames for himself).

At the breakfast tables in Calle Merced a few days later I hear someone refer to San Fermín as ‘Hemingstein’ – that is, a monster of Ernest Hemingway’s making (although it was also one of his favourite boyhood nicknames for himself).English-language writers and filmmakers have been magnetically drawn to the festival since Hemingway chose it as the backdrop to his 1926 novel

The Sun Also Rises, but in the past few years a creative cottage industry has sprung up around it, and bull running in particular.

As well as Bill Hillmann’s latest, this year sees publication of the waggishly smart Bulls Before Breakfast by Peter N Milligan, a Philadelphia lawyer with more than 70 runs under his belt, and the release of a feature-length documentary, Chasing Red, by Dennis Clancey.

Clancey, 32, a West Point graduate who served in Iraq as an infantry platoon leader, came to Pamplona for the first time in 2007, and the desire to capture it hit him hard, though he didn’t know how to. ‘I had no idea.

Clancey, 32, a West Point graduate who served in Iraq as an infantry platoon leader, came to Pamplona for the first time in 2007, and the desire to capture it hit him hard, though he didn’t know how to. ‘I had no idea.I put myself in the film because as a military guy I don’t expect others to take risks that I’m not prepared to take myself. And I knew I could rely on myself to get a big run if the documentary was lacking direction.’

Would Hemingway have approved? Well, at least one Hemingway does. John, grandson of Ernest, has been running with the Pamplona Posse, a loose collective of long-term runners, encierro guides and ‘whole-fiesta-heads’, since 2009. ‘Many people promote their work during the fiesta because there’s quite a bit of media coverage. It’s logical. To say that San Fermín risks overexposure is surreal. It has been “overexposed” for decades.’

Montreal-based John, a writer and general keeper of the family flame, has never felt an obligation as a Hemingway to run or get involved in San Fermín. His attachment to it is the same as mine. ‘I’m here for the camaraderie, the friendships old and new, the atmosphere of a nine-day party that is both a pagan bacchanal and a Christian festival. And of course, the running of the bulls and the afternoon corridas. I love it.’

The corridas – bullfighting – there’s just no avoiding the subject. For the past 14 years, every July 5, the animal-rights group Peta has protestedagainst ‘the shameless, barbaric spectacle’ of the corridas. It has become part of the festival calendar.

The headline-grabbing displays of outrage fromPeta are greeted with amusement or indifference by the locals. This year 100 activists wearing little more than body paint created a ‘river of blood’ outside Pamplona’s bullring, the Plaza de Toros.

After watching a triple bill of celebrity matadors – Juan José Padilla, ‘El Juli’ and Miguel Angel Perera – take on bulls from the Garcigrande ranch, I talk to Alexander Fiske-Harrison, an Old Etonian who runs in his school blazer and whose training as a bullfighter is the subject of his book Into the Arena.

He is a stone-cold pragmatist with a poet’s heart. ‘I’m often asked, why can’t we leave them alone?’ he says. ‘And I tell them that the wild bull, the aurochs, is extinct. Its closest relative, the toro bravo, pays for its five years wild on the ranch with 20 minutes in the ring, just as the beef cow does with its 18 months in the corral or factory farm. And the argument that killing for food is not the same as killing for entertainment is bogus.We eat meat because we like the taste – to entertain our palates.’

Day eight, and it’s my fourth run of the festival. The bulls have been fast and well behaved, though not, it seems, on the days I’ve stayed in bed. The first day, bulls from the Jandilla ranch separated (they normally stick together) tossing their horns – a trait of the breed – and three runners were gored,including Mike Webster, a friend of friends (mercifully, he was able to leave hospital after a couple of days).

I’ve avoided calamity so far but my nerves won’t accept that. I wonder what I’m doing here. I ran my first encierro in 2013, the year I left hospital after having been beaten into a coma by thugs in a London side-street. My daughters half-joked that even multiple bangs on the head had failed to bring me to my senses. The girls are never far from my thoughts, but they are centre-stage right now.

My trouble, perhaps, is that my one fear is a dull death. I think that if I were a bull, I would prefer to perish in the arena, to play my part in some dark art. And that is something I seem to have in common with a lot of people here.

I manage to avoid death, dull or otherwise, but I sustain an injury seconds into my fourth run. With a pair of horns a couple of feet from my rear, I am forcibly sandwiched between a heavy-set man in his mid-50s and some external plumbing on a wall. I feel my chest pop, but it takes a day for the adrenalin that was masking the extent of the damage to wear off. I have two cracked ribs, which make laughter – and yawning, coughing and typing – a distinctly unfunny business.

I manage to avoid death, dull or otherwise, but I sustain an injury seconds into my fourth run. With a pair of horns a couple of feet from my rear, I am forcibly sandwiched between a heavy-set man in his mid-50s and some external plumbing on a wall. I feel my chest pop, but it takes a day for the adrenalin that was masking the extent of the damage to wear off. I have two cracked ribs, which make laughter – and yawning, coughing and typing – a distinctly unfunny business.On my final day in Pamplona, after 10 days of swampy humidity, the weather breaks. It’s an Old Testament production. The rain comes down like judgment on cobbles that appear to bear the imprints of cheeks when wet. Thunder shakes its metal sheet. It sounds like a convoy of bin lorries. Or perhaps a herd of Jandillas.

Pamplona Bull Running

The festival of San Fermín, or the Running of the Bulls as it’s more commonly known outside Spain, officially begins at midday on 6th July every year with the ‘Chupinazo’ which takes place on the balcony of the Casa Consistorial in Pamplona. Thousands of people congregate in the square awaiting the mayor’s official announcement that the fiestas have begun, a rocket is launched and the partying begins.

History of the Running of the Bulls

The history of the bullrunning in Pamplona is not clear. There is evidence of the festival from as far back as the 13th century when it seems the events took place in October as this coincided with the festival of San Fermín on October 10th.

It seems that the modern day celebration has evolved from this as well as individual commercial and bullfighting fiestas which can be traced back to the 14th century.

Over many years the mainly religious festival of San Fermín was diluted by music, dancing, bullfights and markets such that the Pamplona Council proposed that the whole event be moved to July 7th when the weather is far more conducive to such a celebration. To this day San Fermin remains a fixed date every year with the first bullrun at 8am on July 7th and the last at the same time on July 14th.

Short Brief

Like many of the world’s most famous traditions, the annual “running of the bulls” in Pamplona, Spain—the encierro—has somewhat foggy origins.

Each July, thousands arrive from across the world in Pamplona from July 7-14 for the San Fermin Festival, named for the patron saint of the town in Spain’s northern Basque region, and to hear the bulls’ hooves hit the cobblestone streets each morning as they charge toward the bold participants, who run them from a pen to the nearby bull ring, where bull fights commence.

Each July, thousands arrive from across the world in Pamplona from July 7-14 for the San Fermin Festival, named for the patron saint of the town in Spain’s northern Basque region, and to hear the bulls’ hooves hit the cobblestone streets each morning as they charge toward the bold participants, who run them from a pen to the nearby bull ring, where bull fights commence.The tradition may date back to the 13th century and, though it can now sound like a pretty frivolous thing to do (and several runners have died throughout the run’s history) the origins of running with bulls were very practical.

As TIME reported in 1937, the practice of racing in front of bulls to guide them to their pens or ring was in place before the festival began.

It was typically used by cattle herders and butchers attempting to guide bulls from the barges on which they arrived to town, to an enclosure in the middle of the night. It’s not entirely clear when townspeople joined in on the run as a feat of bravery.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Meanwhile, the fiesta of San Fermin was carried on as a religious event intended to honor Pamplona’s first bishop, San Fermin, who was beheaded in France while preaching the gospel in the early the third century.

The event was held in the fall, rather than in July. Eventually, as the run became a Pamplona tradition rather than just a thing that butchers did for work, the more religious aspects of San Fermin and the encierro merged.

The event was held in the fall, rather than in July. Eventually, as the run became a Pamplona tradition rather than just a thing that butchers did for work, the more religious aspects of San Fermin and the encierro merged.The modern running course for the bull run was set up sometime later to prevent bulls from escaping into the streets.

Peter N. Milligan, a 46-year-old New Jersey lawyer and author of the memoir Bulls Before Breakfast,

who has run with the bulls more than 70 times, says townspeople date the modern running course back to 1776, though he admits there aren’t “really good records” for the run’s origins.

The July fiesta in Pamplona was later romanticized by Ernest Hemingway’s visit and resulting novel The Sun Also Rises in 1926, as well as by the countless tales of revelers who had lived to tell their tales.

By now, Pamplona’s isn’t the only bull run in Spain, let alone the world. Even the United States has had a few bull runs of its own — though some, like Milligan, say those aren’t real bull runs.

“Pamplona is like the Super Bowl of the bull runs,” he says.

And there, despite less than glamorous beginnings, tradition endures.

Even today, Milligan says, revelers ask San Fermin for protection and guidance before the run.

i am not responsible Of any Mistake / USE Of any Kind of Bad Words { Wording } / Any Word

Copy Write All ideas Picture & Articles / Data From Google , Wikipedia & Google Sites & Google Others Web Sites

Thanks Read

Always Remember me in your Payers

Muhammad Younis

Trekker & Mountaineer

Comments

Post a Comment